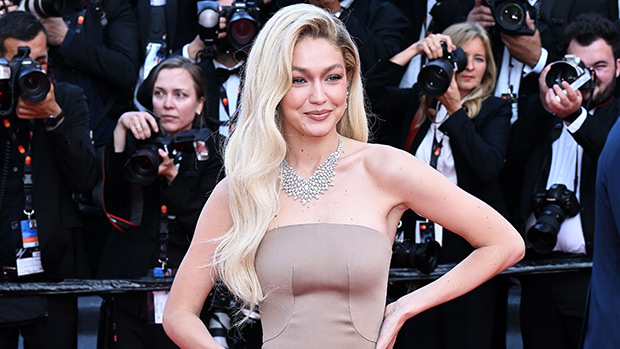

1935’s Particular Agent.

Everett

Published

12 months agoon

By

gosepnews

Martin Scorsese’s adaptation of David Grann’s Killers of the Flower Moon is the newest flip in a protracted movement image custom of pilfering FBI case recordsdata for display eventualities. Initially, Hollywood coveted the validation of the bureau (“based on actual FBI case histories!”) and the private imprimatur of its lord excessive ruler, J. Edgar Hoover (who in 1945 really learn life insurance coverage commercials for NBC radio’s This Is Your FBI). Right now, it usually takes cues with out the official stamp of the FBI protect. Both method, the 2 American establishments have loved a worthwhile relationship.

Created in 1908 throughout the Division of Justice because the Bureau of Investigation and formally branded with the trademark initials in 1935, the FBI grew up through the first wave of digital age media and took full benefit of the coincidence. Hollywood cinema (newsreels, shorts, and have movies), radio crime exhibits, comedian strips and tv sequence cheerfully operated as unpaid publicity for the FBI and the person who presided over it for nearly fifty years. All of the tributaries of the media tracked and facilitated the rise of the company — dramatizing Hoover’s speaking factors in regards to the want for the scientific examine of crime and celebrating the dauntless exploits of its eternally vigilant chief. Solely very late within the recreation did the key studios and broadcast networks solid a extra jaundiced eye on the creature that they had created.

Although an unlikely media star, J. Edgar Hoover was a grasp of manipulation. Born in 1895, an unsocial and unsmiling boy whose greatest pal was certainly his mom, he started his desk-bound profession as a factotum on the Library of Congress, the place he honed his penchant for cataloging info and indexing actuality. Appointed to the Bureau of Investigation in 1917, he specialised in smoking out so-called subversive aliens earlier than, at age twenty-nine, being appointed to go and reshape the company in 1924. It was his life’s work.

Given the brazen corruption and incompetence that had been seen in native legislation enforcement, Hoover’s imaginative and prescient of a centralized headquarters to assemble crime statistics, consider proof and prepare a cadre of forensic-minded specialists made sense. Grann’s guide — a riveting true crime account of the serial killing of oil-rich members of the Osage tribe in Oklahoma within the Nineteen Twenties — helps Hoover’s case. The cold-blooded murders of total Osage households have been a group effort perpetrated by pillars of the white group — aided and abetted by native businessmen, lawmen, medical doctors, and undertakers. In Grann’s telling, the investigation by federal brokers is a quest for justice that additionally serves as a public relations coup for an FBI nonetheless in embryo.

Within the early Nineteen Thirties, the FBI seized a good higher alternative to make its bones. Prohibition had given start to a brand new prison kind, the city gangster, a tommy-gun toting outlaw ready-made for Hollywood’s early sound period. Like their real-life inspirations, the prototypes for an aborning style — Little Caesar (1931), The Public Enemy (1931) and Scarface: The Disgrace of the Nation (1932) — channeled resentment in opposition to a flatlined economic system within the nadir of the Nice Melancholy. American politicians nervous that the identification with the display rebels could be greater than vicarious, particularly with tabloid newspapers barely bothering to hide their admiration for the daring financial institution robbers or their contempt for the native lawmen whose scorching pursuits screeched to a halt at state strains.

Hoover seized the chance. Essentially the most infamous and admired of the gangster breed was the trendy and trigger-happy John Dillinger, a prison so widespread that the Hays workplace forbade Hollywood from producing any movie based mostly on his exploits. Irrespective of: the FBI made certain that Dillinger secured an enduring place in movement image historical past. On the sweltering night of July 22, 1934, after watching MGM’s gangster-themed Manhattan Melodrama (1934) at Chicago’s air-cooled Biograph Theater, Dillinger was gunned down by FBI ambushers led by particular agent Melvin Pervis. Dillinger, Public Enemy No. 1, a brief launched quickly after the execution, delivered the curtain line. Over an image of a really useless Dillinger laid out on a slab within the Chicago morgue, the narrator brags, “The federal government always gets its man!” Emphasis on federal.

For each the FBI and Hollywood, 1934 was a tipping level yr. The Roosevelt administration was vacuuming energy away from cities and states and into Washington, D.C., and among the many many alphabet companies created beneath FDR’s New Deal none would show extra enduring and highly effective than the FBI. In the meantime, in Hollywood, the institution of the Manufacturing Code Administration, headed up by Joseph I. Breen, started to implement its personal form of legislation and order over American cinema. The Breen workplace was hip to the rip-off Hollywood at all times performed within the gangster photos — revel for 85 minutes within the gunplay, quick automobiles, cool garments, and slinky molls earlier than exacting a crime-does-not-pay penalty within the final 5 minutes.

With Breen’s crucial, Hollywood shifted allegiances and embraced the brand new zeitgeist. Even the gangster specialists at Warner Bros. went straight with an act of repentance entitled G-Males (1935). (The time period was coined by a second-rate hood with a first-rate moniker, Machine Gun Kelly, who in 1933 was cornered in his hideout by federal brokers. Reasonably than exit in a blaze of glory, he put up his palms and pleaded, “Don’t shoot, G-men! Don’t shoot!”)

James Cagney performed the lead G-man and the defection to the feds of America’s emblematic display gangster marked a critical cultural turnabout. “Hollywood’s most famous bad man joins the ‘G-Men!’” shouted advertisements. Setting the sample for each pro-FBI movie that adopted, G-Males fixated on the dazzling forensic instruments of the rising surveillance state and fetishized ballistics, lab work and fingerprints (at this time, substitute DNA). “It’s completely on the right side of the law, and hurray for the Department of Justice,” exulted The Hollywood Reporter. Studios round city all obtained with this system: United Artists with Let ‘Em Have It, MGM with Public Hero No. 1, Warner Bros. once more with Particular Agent, and Paramount with Males With out Names (unique title: Federal Dick), all 1935.

1935’s Particular Agent.

Everett

All through the Nineteen Thirties, People couldn’t activate a radio or enter a film home with out being reminded of the crime busting G-Males and the selfless sentinel hailed by syndicated columnist Walter Winchell as “America’s top cop” and “the nation’s Number 1 G-man.”

A Common quick with the why-even-bother title You Can’t Get Away with It (December 1936) is typical. Produced with Hoover’s approval and on-screen participation, it guarantees an unique tour “behind the scenes with the G-Men” on the FBI’s new headquarters, in-built 1935 to Hoover’s specs. The digicam lovingly lingers on file cupboards, crime labs, fingerprint notecards and mug pictures. A squadron of legal professionals, accountants, scientists and switchboard operators stand on the prepared as a result of “the FBI never sleeps!” (All males: there have been no G-women till 1972). On the finish of the tour, Hoover seems to be into the digicam and reminds audiences that “the Federal Bureau of Investigation is as close to you as your nearest telephone” — that means to dial 7117 for assist. The frontier marshal, the county sheriff, the cop on the beat — all have been being supplanted by Hoover’s data-gathering, buttoned-down investigators because the supreme personification of American legislation enforcement.

Throughout WWII, turning from gangsters to Nazis, Hoover solidified his standing as chief protector of the realm. In newsreels, radio spots and display magazines, he appealed to dwelling entrance People to report any suspicious exercise. “Fighting silent battles on a silent front, nearly 4,500 FBI special agents led by director John Edgar Hoover are winning countless victories over the enemy’s invisible army of spies and saboteurs,” declared the March of Time in September 1942, urging moviegoers to “see Uncle Sam’s G-men at war!” Hoover lived as much as the hype: Alfred Hitchcock’s Saboteur (1942) however, no main act of dwelling entrance sabotage occurred on his watch. Henry Hathaway’s The Home on 92nd Avenue (1945) — “made with the cooperation and blessing of J. Edgar Hoover and his FBI organization” — commemorated the FBI’s battle report, telling of how the G-men foiled a plot by Nazi spies to acquire American atomic secrets and techniques. The packed homes for the movie, mentioned a contented exhibitor, “proves that the FBI is SRO.”

1945’s The Home on 92nd Avenue

Within the postwar period, the surveillance equipment put in place to detect Nazi brokers was deployed and expanded to ensnare the brand new risk to home tranquility, actual and imagined, the communist subversives. Hollywood filmmakers, listening to the clicks on their very own telephones and noticing males in brown sneakers and white socks taking down license plate numbers in studio parking tons, responded with a defensive cycle of anti-communist leisure impressed by the exploits of former FBI brokers who parlayed their credentials for private aggrandizement. Among the many choices have been I Was a Communist for the FBI (1951), Stroll East on Beacon (1952), and the tv sequence I Led 3 Lives (1951-53). By then, Hoover was essentially the most unassailable determine in American public life, a real untouchable, past criticism, genuflected to by Republican and Democratic politicians alike.

For Hollywood, the consummation of the love match was Mervyn LeRoy’s The FBI Story (1959), based mostly on the bestselling hagiography by Don Whitehead. At first of the movie, in Technicolor and Cinemascope, Hoover seems briefly at his desk, with wingman Clyde Tolson at his aspect. James Stewart stars as a composite agent whose profession parallels the rise of the company. The historical past in response to Hoover ticks off the chapters in a life inseparable from the job, or somewhat vocation, that’s the FBI: investigations of the KKK, the Osage murders, the Kansas Metropolis Bloodbath of 1933 (the place 4 lawmen have been killed and FBI brokers thereafter obtained the fitting to hold firearms), Nazi spies, and Soviet infiltrators. The pre-credit sequence is the most effective: a tick-tock countdown to a mass homicide that might have been contemporary within the minds of 1959 moviegoers, an insurance coverage scheme by Jack Gilbert Graham (performed by Nick Adams), who in 1954 planted a bomb in his mom’s suitcase earlier than she boarded a flight from Denver; the mid-air detonation killed all 44 aboard. Within the 20 years since G-Males and You Can’t Get Away with It, the company has grow to be much more omniscient, the net of surveillance spiraling outward in wider and wider circles, the march of forensic science closing in with an ever-tightening grip. Because the proof mounts, an agent tells Graham, “We don’t insinuate. We simply collect evidence.” Graham doesn’t stand an opportunity.

1959’s The FBI Story.

The FBI Story marked the high-water mark for FBI worship in postwar American tradition. Within the Nineteen Sixties, the person whose title had at all times been uttered with reverence discovered himself out of sync with the brand new instances. Sycophantic journalists and politicians all of the sudden grew a spine: was it wholesome for a democracy to allow a bureaucrat answerable to nobody? Hoover’s decisive misstep was to smear the activists of the civil rights motion as communist-inspired fifth columnists. “Martin Luther King is a liar,” Hoover snarled in 1964, after King accused the FBI of slow-walking the investigation of the murders of the civil rights staff Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Michael Schwerner. Hoover by no means apologized for, or recovered from, the comment.

To burnish his picture, Hoover coopted the brand new display medium. Nearly because the daybreak of tv, he had sought a chief time showcase for the FBI, however Attorneys Normal beneath Eisenhower and Kennedy had at all times nixed the deal, feeling Hoover’s profile was fairly dominant sufficient. (ABC’s The Untouchables [1959-1963] was based mostly on the exploits of Treasury Division — not FBI — agent Eliot Ness in Prohibition period Chicago, one of many uncommon situations the place the T-men grabbed the highlight from the G-men.) When the Johnson administration relented, Hoover grew to become the de facto showrunner for ABC’s The FBI (1965-1974), which Selection frankly known as “a program designed to pull Hoover’s charred prestige out of the fire.”

ABC’s The FBI sequence, led by Efrem Zimbalist Jr.

Led by straight arrow Inspector Lewis Erskine (Efrem Zimbalist Jr.), the present’s video G-Males steered nicely away from civil rights points and carried out no unlawful bag jobs. Hoover learn the scripts, planted an agent on set as a technical advisor, and made certain his {photograph} loomed backscreen. The sequence was sponsored by Ford, whose president on the time was a former FBI agent, and whose automobiles gave the impression to be the only real automotive model permitted on American roadways.

When Hoover died in 1972, the obituaries have been respectful — how may they not be? Few males in Washington had left behind such a legacy — however there was additionally a palpable sense of aid. In 1967, the passage of the Freedom of Info Act had cracked open Hoover’s secret recordsdata and, even with copious redactions, the inner memoranda revealed an astonishing variety of FBI manhours had been spent chasing down screenwriters somewhat than mobsters. In 1971, revelations in regards to the FBI’s home counter intelligence program (code named CoIntelPro), uncovered the company as a legislation onto itself. In 1975-1976, the Senate Choose Subcommittee to Examine Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Actions, chaired by Sen. Frank Church, held hearings to research the investigators. The findings additional uncovered the FBI (together with different federal initials) as extra-Constitutional branches of what would later be labeled the Deep State.

A brand new technology of Hollywood filmmakers went in for the kill. Larry Cohen’s The Non-public Information of J. Edgar Hoover (1977) was the primary of the key blacklash movies, made when the revelations in regards to the FBI have been nonetheless surprising and the anger nonetheless scorching. The burly, jowly Broderick Crawford is well-cast as a late interval Hoover, raging as a lion in winter, a bundle of neuroses, particularly about ladies. “He was the most feared man in America!” learn taglines. However no extra. Nor was Hollywood any longer parroting the official model. This time the pre-credit scrawl assures moviegoers that “this motion picture was filmed on actual locations of the FBI but without the approval or censorship of the bureau.” Already too, the movie whispered the rumors of Hoover’s homosexuality that might have denied an FBI safety clearance to anybody else in authorities. Within the years since, few retrospective political dramas set within the Nineteen Sixties — Hoffa (1992), Malcolm X (1992), Nixon (1995), Selma (2014) — have omitted a scene that includes J. Edgar Hoover or his minions nefariously pulling strings from behind the scenes to undermine the course of the justice they have been pledged to uphold.

Right now, after all, the political wing as soon as probably to deify the FBI desires to defund it. But for Hollywood filmmakers, whether or not revisionist (Clint Eastwood’s J. Edgar) or celebratory (principally each true crime present “drawn from actual case files!” on A&E and Netflix), the initials nonetheless retain a sure magic. Even cinematic serial killers have proven due respect for the model. “You could only dream of getting out, getting anywhere,” hisses Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs (1991) as he tries to psych out FBI agent in coaching Clarice Starling, realizing her final ambition and savoring every letter, “all the way to the Ef … Be … Eye.”